The ruling states that 'AI companies do not need the author's permission to train AI with legally acquired books'

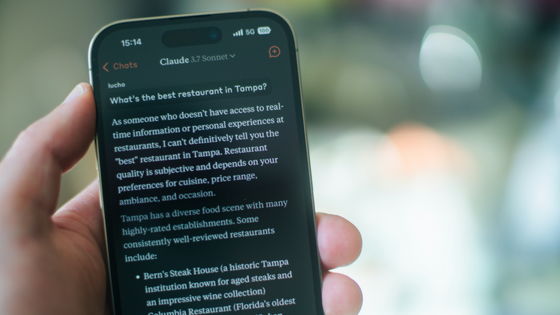

In a case where Anthropic, the developer of the AI chatbot 'Claude,' was sued by three American authors for copyright infringement, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California ruled that 'training an AI with legally purchased books, even without the author's permission, is fair use and does not infringe copyright.'

Authors v Anthropic ruling | DocumentCloud

Anthropic wins a major fair use victory for AI — but it's still in trouble for stealing books | The Verge

https://www.theverge.com/news/692015/anthropic-wins-a-major-fair-use-victory-for-ai-but-its-still-in-trouble-for-stealing-books

Key fair use ruling clarifies when books can be used for AI training - Ars Technica

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2025/06/key-fair-use-ruling-clarifies-when-books-can-be-used-for-ai-training/

Journalists and authors Andrea Bartz, Charles Graeber, and Kirk Johnson filed a lawsuit against Anthropic in August 2024, alleging that Anthropic infringed copyright by using data from pirate sites such as LibGen and Books3, as well as scans of physical books, to train Claude.

Anthropic sued by three authors for copyright infringement, claiming it used hundreds of thousands of copyrighted books to train Claude - GIGAZINE

Anthropic admitted that it had used pirate sites to train Claude, and that it had also purchased, shredded, scanned, and digitized millions of books for use in training him, but argued that this constituted 'fair use' under copyright law.

Judge William Alsup of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California issued three main rulings regarding Anthropic's claims.

1: Training the AI using scans of physical books

Judge Alsup noted that the AI is studying the contents of a book not simply to copy it, but to learn the statistical relationships that allow it to generate entirely new texts, and that the AI's output is not providing users with a copy or plagiarism of the original book.

In response to the plaintiffs' argument that training an AI would lead to a flood of competing works, damaging the market, Judge Alsup said, 'That's no different from complaining that teaching children how to write will create more future competitors. This is not the kind of competitive or creative substitution that copyright law is concerned about. Copyright law is not about protecting authors from competition, but about the advancement of original works.'

2: Scanning and digitizing the books I purchased

The court also found that Anthropic's shredding and scanning of legally purchased physical books was a fair use because Anthropic's purpose and nature were deemed 'transformative.'

'Anthropic already owned the books and destroyed the original physical copies after scanning them. The digitization was intended to conserve storage space and facilitate searching, and because the data was stored in Anthropic's internal research library, it was clear that copies were not intended to be distributed or sold to third parties,' Judge Alsup wrote.

Judge Alsup argued that digitization is a reformatting of a book and does not infringe the copyright owner's distribution rights or derivative work rights.

3. They used pirated sites to train their AI

Anthropic has admitted to downloading millions of books from pirate sites, including Books3 and LibGen, and while it acknowledges that 'in its position in this lawsuit, it acknowledges that its use of the pirate site data was malicious,' it argues that malicious intent does not prevent its use from being fair.

However, during the trial, it was pointed out that there were voices within Anthropic that were reluctant to use such data due to legal issues. Judge Alsup clearly ruled that 'Anthropic's act of downloading over 7 million books from pirate sites to build a central library was not fair use.' He stated that the library built with data from pirate sites served as a 'substitute for paid copies' and was not transformative.

Anthropic also decided that it would not use certain books for training or would never use them again, but continued to keep the materials in its library. This means that the purpose of the copies was not limited to training, Judge Alsup pointed out, and argued, 'The fact that some copies will be used in the future to train AI does not justify the initial illegal copying. You cannot just take away any textbook you want just because you have a research purpose. If that were the case, the academic publishing market would be destroyed.'

The court's decision that using legally collected books to train AI is fair use and does not require permission from the authors is a major victory for Anthropic and other AI companies.

Anthropic told The Verge, an IT news site, 'We are pleased that the Court has recognized the use of copyrighted work to train large-scale language models as 'transformative.' Anthropic's AI was trained not to replicate or replace prior copyrighted work, but to break new ground and create something different, in line with copyright's purpose of enabling creativity and promoting scientific progress.'

On the other hand, because Anthropic's use of the pirated site's data constitutes complete copyright infringement, Judge Alsup stated that 'Anthropic will be tried separately for the pirated content it used, and the amount of damages will be determined accordingly.' However, if Anthropic later purchased the same books as the pirated data, 'this does not absolve Anthropic of liability for theft, but it may affect the amount of statutory damages.'

Related Posts: