What are the myths and truths about the legendary continent 'Atlantis'?

The Truth about Atlantis - Tales of Times Forgotten

https://talesofttimesforgotten.com/2019/03/26/the-truth-about-atlantis/

A 2014 survey by Chapman University in the United States found that 63% of Americans agreed with the idea that an advanced ancient civilization like Atlantis once existed, and a 2018 survey found that 57% of Americans agreed with the idea. 'These numbers are staggering, given that Atlantis is a complete fiction,' McDaniel said.

Atlantis was described in Plato's books ' Timaeus ' and ' Critias ' as 'a continent and a civilization that had built a mighty civilization.' In the dialogue 'Timaeus,' Socrates raises the topic of 'what would an ideal state be like,' and Plato's great-grandfather Critias tells him that he knows just such a story, and tells him about Atlantis, claiming that it is 'without a doubt true.'

Those who claim that Atlantis was real often argue that Plato was a philosopher, not a writer, and therefore could not have made up stories to pass off as fact. For example, the 1999 best-seller Ancient Mysteries by Peter James and Nick Thorpe states that 'Plato always added his own interpretations to traditional sources, but he has never been shown to have engaged in wholesale fabrication.'

On the other hand, McDaniel points out that 'the idea that Plato did not create stories is a misconception; inventing elaborate stories to illustrate philosophical points is Plato's philosophical style.' For example, in the middle dialogue '

McDaniel also pointed out that the situation in 'Timaeus,' in which the story of Atlantis is told, is itself fictional. 'Timaeus' records a dialogue between Socrates, Plato's great-grandfather Critias, Timaeus, a notable figure from the ancient city of Locris in central Greece, and politician and soldier Hermocrates, but there is no evidence that this dialogue actually took place. In particular, while Critias, Hermocrates, and Socrates are recorded outside of Plato's works, Timaeus is considered to be a fictional character because there is no independent mention of him outside of Plato's works.

In Timaeus, Critias claims to have heard the story of Atlantis from his grandfather, who in turn heard it from his father. Critias' great-grandfather is said to have heard it from the ancient Athenian statesman Solon , but McDaniel says that none of the many surviving poems related to Solon mention Atlantis. 'How can we take seriously the claims that the story being told is true when the dialogue depicted is itself fictional?' he says.

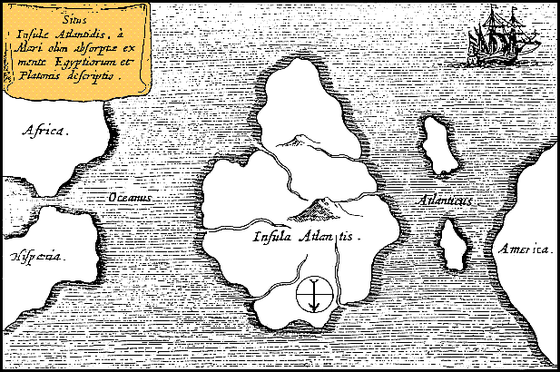

Furthermore, McDaniel lists not only literary and historical reasons but also scientific reasons why the story of Atlantis cannot be historically true. Of particular note is that Plato describes Atlantis as a 'huge island located in the Atlantic Ocean just beyond the Strait of Gibraltar,' a location that contradicts modern scientific understanding of plate tectonics. There was no scientific basis to refute Plato's claims in the past, but based on the theory of continental drift proposed by German meteorologist Alfred Wegner in 1912, there would not have been enough space in the Atlantic Ocean for the 'huge lost continent' described by Plato to exist.

Some supporters of the existence of Atlantis, even after hearing the scientific evidence of the denial theory, suggest that Plato's description is a result of misunderstandings and discrepancies in information passed down through oral tradition, and that Atlantis actually existed in a different place and in a different form. In 1909, classical scholar K. T. Frost proposed that Atlantis referred to the Minoan civilization . This theory was greatly advanced by the 1939 conclusions of Greek archaeologist Spiridon Marinatos, who excavated a Minoan settlement on the north coast of Crete. However, there is a big difference in size and time of demise between the Atlantis described by Plato and the Minoan settlement, so 'it is unlikely that Plato was influenced by the Minoan civilization,' says McDaniel.

If Atlantis is a fictional city, its image is thought to be an 'allegory of state tyranny.' In fact, McDaniel points out that some of Plato's descriptions of Atlantis talk about Athens rather than Atlantis, and that the 'ideal state' refers to Athens, not Atlantis. According to McDaniel, Plato's Atlantis story is essentially a 9,000-year-old transplant of the Persian Wars , replacing the Achaemenid Empire with the Atlantean Empire.

McDaniel believes that the account of Atlantis is a deliberate fiction based on modern history at the time, intended to convey a philosophical message. One of Plato's most famous doctrines is the doctrine of ideas , which holds that behind every phenomenon in the real world there exists an unchanging and eternal essence of 'idea.' McDaniel says, 'For Plato, even reality itself was in some sense symbolic. Atlantis is an allegory that symbolizes every empire, every nation, every tribe that once existed but no longer exists.'

in Note, Posted by log1e_dh